Abstract:

The week of July 12 will mark the 28th anniversary of the Chicago Heat Wave of 1995, during which more than 700 people lost their lives, predominantly the elderly and vulnerable. The disaster highlighted various factors that contributed to its impact, such as political influence, budget cuts, climate change, socioeconomic status, and media recognition. Effective and timely information dissemination by the media is crucial in a crisis. Despite being one of the deadliest crises in the United States, heat waves often lack visual stimuli that prompt immediate action. The media's portrayal of heat waves often focuses on leisure activities rather than highlighting the danger. Media agendas, sensationalism, and political framing can hinder the communication of emergency threats. Isolation and community fabric deterioration increase the vulnerability of older adults during heat waves. Identifying at-risk individuals and communities before a crisis can aid in targeted assistance. The relationship between the media and emergency managers is often contentious due to conflicting priorities and narratives. Media sensationalism and framing can distort the perception of risk. Standardized statements relayed by media entities during emergencies could cut through political biases. Further research is needed on heatwave-specific communication and risk perception stimuli, as well as the effectiveness of visual stimuli in triggering survival responses.

Introduction

The week of July 12 will mark the 28th anniversary of the Chicago Heat Wave of 1995 - in which more than 700 lost their lives. The isolated, elderly, and vulnerable constituted most of these heat-related fatalities (Klinenberg, 2015). Although it affected multiple cities in the region like Milwaukee (CDC, 1996) and Danbury (Coleman, 1995), the crisis is best known for its human impact on the “Windy City,” which saw a peak heat index of 125 degrees (NWS, n.d.-b). While many initially sought to claim its fatal consequences as an “act of God '', Erik Klinenberg - a world-renowned sociologist and expert on this event – disagreed (Klinenberg, 2015). Not unlike other disasters, a multitude of prerequisites shaped its formation and consequences, whether it be political influence and accountability, resource and service budget cuts, climate change, socio-economic and communal status, age and sex, or threat recognition by the media (or lack thereof) - to name a few.

The importance of effective and timely information dissemination before, leading to, and during a crisis cannot be understated and warrants a closer examination of the media’s critical role in the disaster.

Background:

The summer had been unusually hot globally – with places like India (Bedi, 1995; Wagner, 1995) and the United Kingdom (Stinger, 1995; Leicester Mercury, 1995) experiencing above-average high temperatures in the weeks and months leading to the Chicago crisis. As the heatwave developed [NOAA, n.d.], the National Weather Service began issuing warnings to public officials and the media alike. While there is a multitude of reasons why these notifications largely went unheeded, it is evident that the agency did not anticipate the seeming lack of newsworthiness of the creeping crisis in a place like Chicago, whose headlines were full of ongoing and attention-grabbing violence at the time (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1995). Many deaths could have been prevented had the very media - which Chicagoans relied upon as critical information disseminators – prioritized these warnings promptly and effectively.

Heatwaves, in general, are amongst the deadliest crises in the United States (NWS, n.d.-a). Yet, – even with prior warning – there appears to be little progress in mitigating its fatal consequences, especially among the elderly and vulnerable. It is, therefore, important for emergency managers to understand why these communication challenges persist.

Role of Visual Stimuli for Perceived Threats

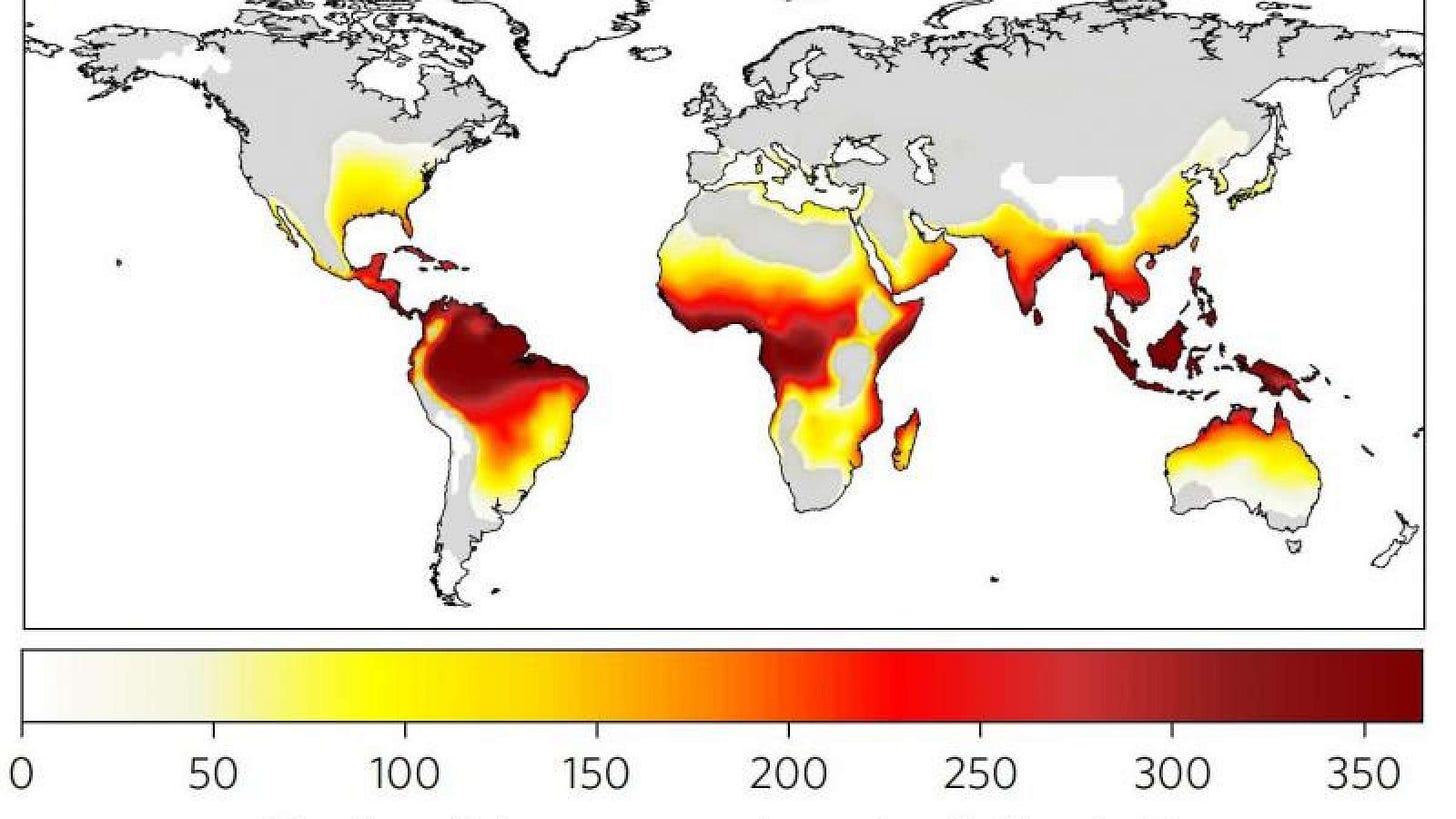

Organisms that use vision as a primary method of navigating the environment (such as humans) heavily rely on the sense to warn them about imminent risks to their safety and survival (Balban et al., 2020). Visual perception is so important for survival that animals use stealth and camouflage to go under the radar. Unlike most threats to human life and safety, heat waves often lack the visual stimuli that compel us to take immediate protective action (McLoughlin, Howarth & Shreedhar, 2023). When was the last time you saw a picture of a heatwave that accurately promoted its danger to health and safety?

The media representations of the current Texas heatwave look much like those of the Chicago disaster in that the affected regions are often indicated by map illustration, and the pictures showcased are of leisure activities. It is difficult to imagine this type of visualization representative of headlines for other disasters such as wildfires, storms, blizzards, cyclones, floods, earthquakes, or even smog. They do not elicit the same response in the audience (Mclouglin & Corner, 2020). Perhaps for this reason, we are captivated by dramatic and emotional stories that stimulate the brain’s visual cortex and amygdala – where the fight or flight responses originate (Eisensee & Stromberg, 2007; Šimić et al., 2021).

Media Undertones and Influences

Agendas and egos in the media are inherent obstacles in communicating EM-based threats to the prospective audience. Because much of the population relies on established media companies, networks, and reporters (who cover a wide range of political topics), their ability to effectively act as a trusted and accurate communication liaison to the public is compromised.

Analogically speaking, it is akin to the story of the boy who cried wolf for attention. After a while, this act of heightening the attention becomes the status quo and ultimately limits the ability to take actual hazards seriously. Now consider the added political and sensationalistic framing dimensions to the equation, and you can start to see why people are likely to dismiss warnings as overblown.

This may be especially true regarding non-visible life-safety threats like heat waves. When we must rely on trusting what people say (instead of seeing it for ourselves), it is easy to let confirmation bias infiltrate our perception of risk. Studies on heatwave communication in the media have proved that (Hanson-Easey et al., 2019).

After all, seeing is believing.

Lessons for the Elderly, Vulnerable and Isolated

As you may recall, most of the heatwave fatalities in 1995 were older adults. While Erik Klinenberg (2015) notes various reasons for this phenomenon, evidence and personal accounts suggest that isolation factors (especially in areas experiencing a community fabric deterioration) were its primary reasons. Research done by Akompab et al. (2013) further shows that people living alone are less likely than their counterparts to accurately perceive heat waves as a threat to their life and safety.

Like the broken windows theory of policing, the fatalities data of the 1995 Chicago Heatwave seem to suggest that higher at-risk individuals and communities may be identified before the onset of a crisis. Many states, like Florida, maintain voluntarily registerable databases for those who may require additional assistance in a disaster (Florida Department of Health, n.d.). A similar concept could also be employed here with volunteer and community civic organizations being utilized for manpower. Not only would these interactions be helpful to resident socialization, but analytics sourced from the encounters may also aid in additional hazard communication research.

Lessons for Partnering with Mass Media

The relationship between the media and emergency managers has been and will likely continue to be contentious for the foreseeable future (Ali, 2013). While both seek to engage the audience through information dissemination, they approach events with conflicting priorities, narratives, and objectives. From a media perspective, disasters require few organizational resources to display visually stimulating storytelling and coverage through which its framing can be controlled and fill airtime. The entertainment business – news outlets included – have often sought to cover and depict disasters through the lenses of “tragedy, chaos, suffering, love and courage acted out by a menagerie of heroes, villains, fools, cowards and scoundrels.” (Wenger, 1985) Emergency managers, at least in the past, have viewed this sensationalized reporting as harmful to active response and recovery operations, as well as to event transpiration and myth perpetration, categories which carry implications for future public official, communal and individual behavior (Ali, 2013).

Part of the media’s goal is to entertain their audience – especially in today’s highly politicized environment – so it becomes difficult for the audience to distinguish true risk from sensationalism. Alarmist mentality perpetration is made significantly worse by middlemen such as journalists, politicians, celebrities or even the media organizations themselves attempting to frame the information to fit their cultivated underlying narratives and talking points (Ali, 2013; Boykoff, 2007; Boykoff & Goodman, 2009; O’Neil et al., 2013).

While Queen Elizabeth’s death may initially seem irrelevant here, there exists an opportunity for inspiration from the choreographed plan it subsequently activated – Operation London Bridge. A preapproved and distributed statement was broadcast to the public across all media platforms in the country. Television and radio hosts read an identical statement – which had been regularly rehearsed behind the scenes for years. The event was above politics, and it was not until later that middlemen and narrative framing got intimately involved. Regarding imminent and active hazards that humans find difficult to accurately perceive as significant threats to their life safety (i.e., heatwaves), media entities in the affected region could be asked to relay a standardized statement to their audiences. The goal here would be to subconsciously establish that the information being presented is so important that it cuts through politics. Immediately trailing that message, a request to do the following could be employed:

Check-in on elderly neighbors and relatives

Provide suggestions on methods to keep cool.

Advise people to visit the local EMD website to locate the nearest emergency cooling centers.

Lessons in Research

Despite its vast beneficial implications, it is evident that the Emergency Management sector lacks sufficient research into heatwave-specific communication and risk perception stimuli. Therefore, the following hypotheses, if researched, could provide invaluable insight into this matter:

Certain image-based representations of heatwaves are most effective in triggering fight-or-flight survival mechanisms.

Visual stimuli-based media consumption vehicles are most effective in eliciting an immediate actionable fight or flight response reaction.

As an individual age, eyesight becomes increasingly relied upon to identify and act upon immediate threats to psychological self-preservation and survival mechanisms.

Corrected for underlying medical conditions and personal senses of vulnerability, those with vision impairments are more likely to prepare for and survive heat waves and other “invisible” hazards than their peers.

Important Note: Although research into climate change-based imagery and risk association already exists, the vast majority of their premises are fundamentally different from the information being sought about heatwaves specifically (such as in the hypotheses above).

They are often based on surveys (Q-Sorting/Sentiment Analysis): Unlike with heatwaves and other similar imminent threats to life safety, surveys cannot provide the accurate subconscious cause and effect-driven data being sought. Instead, they rely on opinions, an endeavor that fails to illustrate exactly which visual stimuli may have induced the psychological phenomena being pursued.

They use non-abstract imagery: Heatwaves are challenging to depict photographically or illustratively. Whereas pictures showcasing flooding or deforestation - for example - can intrinsically promote an underlying message or idea.

Risk Perception: Whereas climate change is commonly viewed as a long-term and societal issue, heatwave-associated imagery – not having that same connotation – can be utilized to control for population-specific factors such as age, sex, political affiliation, community, and culture.

Further Additional Reading:

‘Amber Alert’ or ‘Heatwave Warning’: The Role of Linguistic Framing in Mediating Understandings of Early Warning Messages about Heatwaves and Cold Spells https://academic.oup.com/applij/article/43/2/227/6294004

“Can You Take the Heat?” Heat-Induced Health Symptoms are Associated with Protective Behaviors https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-18-0035.1

Advocacy Messages About Climate and Health are More Effective When They Include Information About Risks, Solutions, and Normative Appeal: Evidence from a Conjoint Experiment https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100030

A Five-Steps Methodology to Design Communication Formats that can Contribute to Behavior Change: The Example of Communication for Health-Protective Behavior Among Elderly During Heat Waves https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017692014

American Red Cross - Closing the Gaps: Advancing Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery for Older Adults https://www.redcross.org/content/dam/redcross/training-services/scientific-advisory-council/253901-03%20BRCR-Older%20Adults%20Whitepaper%20FINAL%201.23.2020.pdf

Changing Behavioral Response to Heat Risk in a Warming World: How Can Communication Approaches Be Improved? https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.819

FEMA Guide to Expanding Mitigation: Making the Connection to Older Adults https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_mitigation-guide_older-adults.pdf

Heat protection behaviors and positive affect about heat during the 2013 heat wave in the United Kingdom https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953615000556?via%3Dihub

Heatwave Early Warning Systems and Adaptation Advice to Reduce Human Health Consequences of Heatwaves https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8124623

Increasing the Reach and Effectiveness of Heat Risk Education and Warning Messaging: Recommendations from San Diego County, California, Residents https://www.dri.edu/wp-content/uploads/Increasing-the-Reach-and-Effectiveness-of-Heat-Risk-Education-and-Warning-Messaging-English.pdf

Mapping Heatwave Health Risk at the Community Level for Public Health Action https://ij-healthgeographics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1476-072X-11-38

Minimization of Heatwave Morbidity and Mortality https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749379712008781

News Media and Disasters: Navigating Old Challenges and New Opportunities in the Digital Age https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-63254-4_23

Old Media, New Media, and the Complex Story of Disasters https://oxfordre.com/naturalhazardscience/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389407-e-21?mediaType=Article

On Heatwave Risk Communication to the Public: New Evidence Informing Message Tailoring and Audience Segmentation https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/media/7369/scott-hanson-easey.pdf

Perceptions of Heat-Susceptibility in Older Persons: Barriers to Adaptation https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph8124714

Predictors Associated with Health-Related Heat Risk Perception of Urban Citizens in Germany https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030874

The Driving Influences of Human Perception to Extreme Heat: A Scoping Review https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111173

The Role of Pictures in Improving Health Communication: A Review of Research on Attention, Comprehension, Recall, and Adherence https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004

Visual Portrayals of Fun in the Sun in European News Outlets Misrepresent Heatwave Risks https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12487

References:

Akompab, D. A., Bi, P., Williams, S., Grant, J., Walker, I. A., & Augoustinos, M. (2013). Heat waves and climate change: Applying the health belief model to identify predictors of risk perception and adaptive behaviours in adelaide, australia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(6), 2164–2184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10062164

Ali, Z. S. (2013). Media Myths and Realities in Natural Disasters. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(1), 125–133. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zarqa-Ali-2/publication/283430024_Media_myths_and_realities_in_natural_disasters/links/60be066c458515218f9b04e2/Media-myths-and-realities-in-natural-disasters.pdf

Al-nuwaiser, W. M. (2022). Effect of visual imagery in COVID-19 social media posts on users’ perception. PeerJ Computer Science, 8, e1153. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.1153

Balban, M. Y., Cafaro, E., Saue-Fletcher, L., Washington, M. J., Bijanzadeh, M., Lee, A. M., Chang, E. F., & Huberman, A. D. (2021). Human responses to visually evoked threat. Current Biology: CB, 31(3), 601-612.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.11.035

Bedi, R. (1995, April 15). India Braced for Heatwave. The Daily Telegraph , 51. https://www.newspapers.com/image/751821625/?terms=heatwave%20india&match=1

Boykoff, M., & Goodman, M. K. (2009). Conspicuous Redemption? Reflections on the Promises and Perils of the Celebritization of Climate Change. Geoforum. 40. 395-406. 10.1016/j.Geoforum.2008.04.006.

Boykoff, M. T. (2007). From Convergence to Contention: United States Mass Media Representations of Anthropogenic Climate Change Science. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32(4), 477–489. http://wjsmith.faculty.unlv.edu//smithtest/BoykoffClimateMedia200722.pdf

CDC. (1996). Heat-Wave-Related Mortality—Milwaukee, Wisconsin, July 1995. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report , 45(24), 505–507. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00042616.htm

Coleman, T. W. (1995, July 16). Hot, Hotter, Hottest at 106. The Hartford Courant. https://courant.newspapers.com/image/176857819/?terms=Hot%20Hotter%20Hottest%20at%20106&match=1

Eisensee, T., & Strömberg, D. (2007). News Droughts, News Floods, and U. S. Disaster Relief. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 693–728. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25098856

Florida Department of Health. (n.d.). Florida Special Needs Registry. https://snr.flhealthresponse.com/

Hanson-Easey, S., Hansen, A., William, S., & Bi, P. (2019). Communicating About Heatwaves: Risk Perception, Message Fatigue, and Threat Normalization. University of Adelaide School of Public Health . https://www.unisdr.org/preventionweb/files/63721_communicatingaboutheatwaves.final.pdf

Klinenberg, E. (2015). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago (Second edition). University of Chicago Press.

Leicester Mercury . (1995, May 13). Gardeners Feel Draft as Weather Changes. 5. https://www.newspapers.com/image/866491537/?terms=heatwave%20&match=1

McLoughlin, N., Howarth, C., & Shreedhar, G. (2023). Changing behavioral responses to heat risk in a warming world: How can communication approaches be improved? WIREs Climate Change, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.819

Mclouglin , N., & Corner, A. (2020). The Air That We Breathe. Climate Outreach. https://climatevisuals.org/the-air-that-we-breathe/

NOAA. (n.d.). NOAA NWS NCEP Reanalysis Data by NCEP WPC [Data set]. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.wpc.ncep.noaa.gov/ncepreanal/

NWS. National Weather Service. (n.d.-a). Heat Safety Tips and Resources. National Weather Service. https://www.weather.gov/safety/heat

NWS. National Weather Service. (n.d.-b). Historic July 12-15, 1995 Heat Wave. National Weather Service (Chicago). https://www.weather.gov/lot/1995_heatwave_anniversary

O’Neill, S. J., Boykoff, M., Niemeyer, S., & Day, S. A. (2013). On the Use of Imagery for Climate Change Engagement. Global Environmental Change, 23, 413–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.11.006

Šimić, G., Tkalčić, M., Vukić, V., Mulc, D., Španić, E., Šagud, M., Olucha-Bordonau, F. E., Vukšić, M., & R. Hof, P. (2021). Understanding emotions: Origins and roles of the amygdala. Biomolecules, 11(6), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11060823

Stringer, G. (1995, May 5). Watch that Sun in the Heatwave. Evening Sentinel, 20. https://www.newspapers.com/image/808105346/?terms=heatwave&match=1

U.S Department of Commerce. (1995). July 1995 Heat Wave [Natural Disaster Survey Report]. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.weather.gov/media/publications/assessments/heat95.pdf

Wagner, T. (1995, June 17). Heat Wave Searing India. The Herald Sun, 4. https://www.newspapers.com/image/792232340/?terms=heatwave%20india&match=1

Wenger, D. (1985). Mass Media and Disasters (No. 98). Disaster Research Center. https://udspace.udel.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/15e1ad24-6209-425e-825f-a7f1d77ad161/content

I saw this posted today (7/6/23) on the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists blog (originally published at Grist): "Extreme heat will cost the US $1 billion in health care costs — this summer alone" - https://grist.org/health/extreme-heat-will-cost-the-us-1-billion-in-health-care-costs-this-summer-alone/

As is true for all incidents/emergencies/disasters/etc. - every one has an ESF#8 - Public Health impact. And Heat Waves will impact hospitals, healthcare systems, etc., including their own Emergency Management (as compared to the obvious impact to their Emergency Departments) capabilities and missions.